Created: 11/1/2022

Javascript Build Tooling

Javascript build toolchains; circa 2015-2022 and beyond

Javascript build toolchains; circa 2015-2022 and beyondI'll reference the companion repo a bit; feel free to download and follow along.

History Lesson

The Auth0 blog has a great Javascript history lesson. In particular, it's important to understand the co-evolution of browsers and transpilers. Here are a few highlights.

ECMAScript 3 was released in December 1999.

This version of ECMAScript spread far and wide. It was supported by all major browsers at the time, and continued to be supported many years later. Even today, some transpilers can target this version of ECMAScript when producing output. This made ECMAScript 3 the baseline target for many libraries, even when later versions of the standard where released.

The next section's TL;DR is that ES4 was a dumpster fire. It was very ambitious, none of the browsers had the motivation to implement it, and all progress on the Javascript language stalled from about 2000-2015. This was also before Node.js, whose v1 release was 2011.

ECMAScript 5: The Rebirth Of JavaScript

After the long struggle of ECMAScript 4, from 2008 onwards, the community focused on ECMAScript 3.1. ECMAScript 4 was scrapped. In the year 2009 ECMAScript 3.1 was completed and signed-off by all involved parties. ECMAScript 4 was already recognized as a specific variant of ECMAScript even without any proper release, so the committee decided to rename ECMAScript 3.1 to ECMAScript 5 to avoid confusion.

ECMAScript 5 became one of the most supported versions of JavaScript, and also became the compiling target of many transpilers. ECMAScript 5 was wholly supported by Firefox 4 (2011), Chrome 19 (2012), Safari 6 (2012), Opera 12.10 (2012) and Internet Explorer 10 (2012).

In other words, we already know today (11/1/2022) what will be released in ES2023, and what is very likely to be included in ES2024. With babel, you can start using these new language features right now. Babel can transform Javascript such that it will run using old ECMAScript features, but you can write the new ones. This desire to use the latest and greatest was one factor that motivated developers to accept the complexity of a new build toolchain.

Also, ECMA is the European Computer Manufacturers Association. They arbitrarily became the standards organization that decides what Javascript is; just like how C is standardized by ANSI (American National Standards Institute), Unicode is standardized by ISO (International Organization for Standards), et cetera.

2015: React & Javascript Framework Wars

Although the latest and greatest ECMAScript APIs were attractive, nothing was as alluring a motivation for adopting build toolchains as React, Vue, Angular, and the 4,353,643 other Javascript frontend frameworks that have risen (and sometimes fallen) over the last 7 years.

Don't get me wrong,

String.prototype.matchAll

is cool and all, but there's no version of ECMAScript where this is OK:

const message = 'Hello, world!';

return (

<div className="container">

{message}

</div>

)

In addition to turning ES2045 into ES1999, babel can also turn the above code into the below code:

import React from 'react';

const message = 'Hello, world!';

return React.createElement('div', { className: 'container' }, [message]);

Oh, I'm sorry, did you think it was React who delivered the magic that made

HTML-in-Javascript work? Nope! In fact, the rest of this story is

absolutely a story of composition. Each build tool has a narrow focus, and

together they create the experience that we know and hate

love.

Create React App

Create React App is a CLI tool for scaffolding out boilerplate of a React application. The toolbox it uses to turn React code into something you can ship to Internet Explorer 9 is likely the most common one used in the react ecosystem, so let's learn its components.

The CRA stack is comprised of webpack, babel, sometimes typescript via ts-loader, a bunch of webpack plugins, and a bunch of glue code scripts written by the CRA team.

Webpack

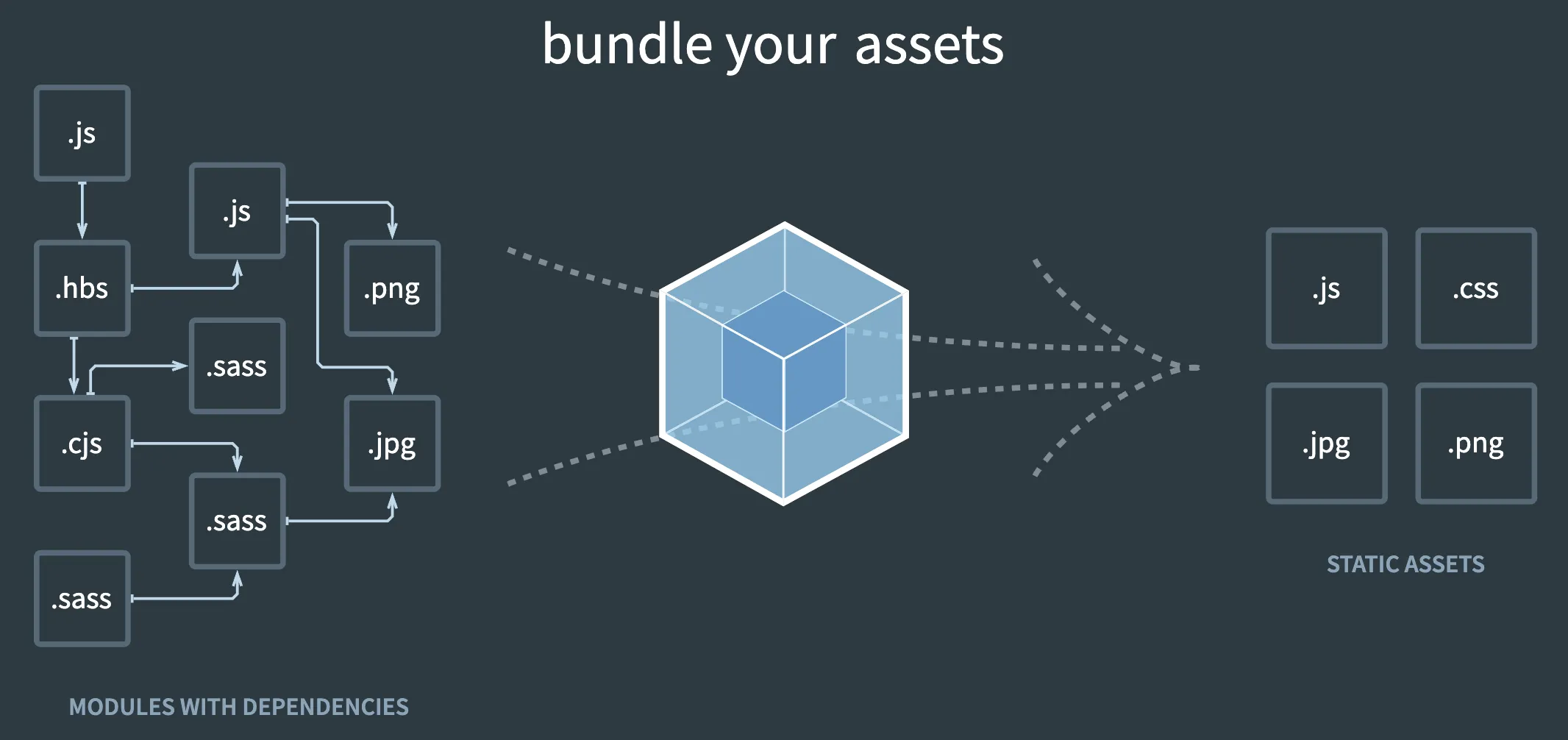

The picture on their home page is a great visual of what webpack does.

Natively, webpack is basically a dumb compiler. The only thing it can do is follow import statements in Javascript code, and glue those many source files into a single bundle. It accomplishes that by taking your code and wrapping it in some webpack code.

In the companion repo's webpack subdirectory,

there is a super minimal webpack usage, so you can see how webpack works.

Notice the difference in output for the build:dev versus build:prod

scripts.

Babel

As we said before, babel is the thing that transforms your Javascript code to standardize it for all browser environments, and also to convert JSX to regular Javascript. I linked to the babel compiler explorer above, so you can explore exactly how babel works.

ts-loader and Webpack Plugins

In the ts-loader directory of the companion

repo, you can see that we

create a webpack config for the first time, and add ts-loader, allowing

webpack to now transparently load typescript files, and allow interoperation

between javascript and typescript. Overall, webpack plugins create "magic

imports" in Javascript, where we can import any file type and webpack will do

magic behind the scenes.

The typescript compiler even has support for typing these "magic modules" that often appear in the webpack world; although they were less fun and named the feature "ambient modules"

Plain Typescript

It's also worth understanding that typescript is a thing in and of itself. You

don't need ts-loader and webpack for typescript. The typescript directory

of the companion repo has an

example where we use typescript by itself.

A Bunch of Webpack Plugins and Glue

Unfortunately, this is what bridges the gap between what we've discussed so

far, and create-react-app. CRA naively tries to hide this complexity from you,

but if you npm run eject on an app made with create-react-app it'll spill

that complexity right out into your codebase, giving you a gigantic glob of

garbage to try to maintain and understand.

This code is gnarly, and only seems to become worse over time as it inevitably

accumulates fire-extinguishing patches. However, we have covered all of the

core building blocks. To see a concrete example, let's use a 1st party webpack

plugin: file-loader. Again, look in the companion repo for

webpack_plugins_file_loader.

Here, the file loader includes a string to any imported files, and webpack also

deals with putting the included files into the dist folder, as well as

including a hash of the file in the outputted filename, which is useful for

cache invalidation when the file changes.

While we're at it, we will also need the webpack copy plugin to move an

index.html from the src to dist folder, and voila, we have a static site!

Hello there

Hello thereWrap-Up

This has been a summary of the Javascript build system typical of create-react-apps. If you're creating a new Javascript app today, you're best off using Vite for a single-page static site, or Next.js for a full-stack application. I'm sure that the Babel + Webpack stack will have a lot of staying power for years to come. Although we gripe about them, these tools are highly flexible and dynamic, albeit low-level and burdensome at the same time -- a classic trade-off.